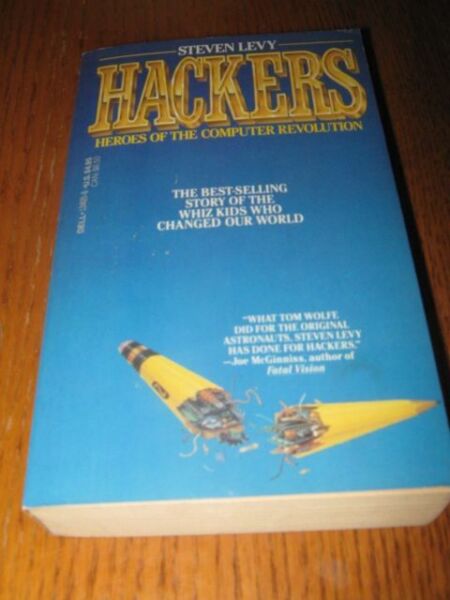

But as I researched them, I found that their playfulness, as well as their blithe disregard for what others said was impossible, led to the breakthroughs that would define the computing experience for millions of people. When I embarked on my project, I thought of hackers as little more than an interesting subculture. I hadn't expected to reach that conclusion. My editor had urged me to be ambitious, and so I shot high, crafting a 450-page narrative in three parts, making the case that hackers - brilliant programmers who discovered worlds of possibility within the coded confines of a computer - were the key players in a sweeping digital transformation. The book I was writing, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, came out just over 25 years ago, in the waning days of 1984. But by then I was convinced that I was documenting a movement that would affect everybody. Gates himself saw my reverence as an intriguing novelty. I saw his passion for computers as a matter of historic import. I would interview Gates many times over the years, but that first conversation was special. His name was not yet a household word even Word was not yet a household word. Back then, Gates had just pulled off a deal to supply his DOS operating system to IBM. I was trying to capture what I thought was the red-hot core of the then-burgeoning computer revolution - the scarily obsessive, absurdly brainy, and endlessly inventive people known as hackers. It's weird how old this industry has become." The Microsoft cofounder and I, a couple of fiftysomething codgers, are following up on an interview I had with a tousle-headed Gates more than a quarter century ago. When we did the microprocessor revolution, there was nobody old, nobody. "When I was young, I didn't know any old people.

Gallery Gates, Zuckerberg Meet for Wired Cover Shoot"It's funny in a way", says Bill Gates, relaxing in an armchair in his office.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)